How internet ads work

Since money was invented, people felt the urge to advertise their products to others. I live very near to Pompeii (Italy) and if you visit this incredible town you'll discover that in 79 a.D. there were a lot of ads painted on walls, trying to sell you wine, prostitutes, or ask for a vote.

Fast-forward a couple of millenia, we have many websites that are free to their users - think at your favourite newspaper. This is totally different from how newspapers made money few years ago: you had to buy them in shops. So, how they pay salaries to their employees now?

You can guess - since it's the topic of this post - many websites earn money by displaying ads. So here's an engineering point of view of this world.

This year I started working for an adtech company and this post tries to describe what I've learned of this mega-curious world.

How were ads in 1999?

In 1999 I was 14 years old, so what I know is based on the tales of wise old men. When a news company launched a website, it had to find advertisers that wanted to display ads on their website. The news company, in adtech words, is called publisher. Many publishers had sales teams that contacted advertisers directly, trying to make a deal like "Publisher will display 1,5 million impressions of these images (in adtech terms: creatives) and Advertiser will pay 100k bucks".

Once the deal was closed, there were needs to:

- track impressions - how many times ads were rendered? and how many times they were actually viewed? and clicked?

- handle multiple campaigns concurrently - I can close a deal with advertiser A for 1.5mln impressions per 100k, but then close another deal with advertiser B for 500k impressions for 200k - which one would you show most? and with what algorithm?

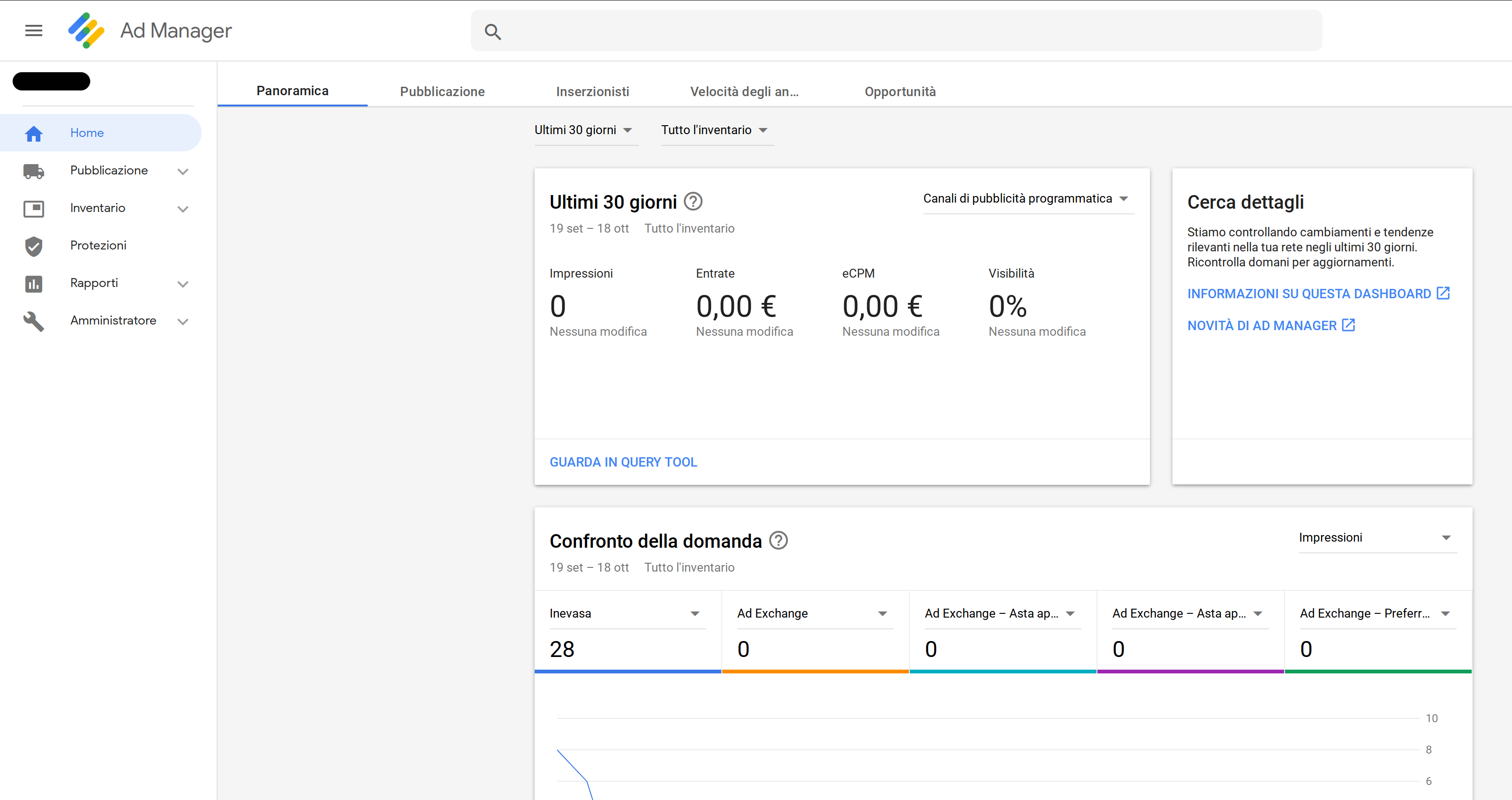

Turns out, you need a software to implement these logics. A software like that is called Ad Manager. One of the most famous ad managers is...

Doubleclick for Publishers

DoubleClick for Publishers, also known as DFP, has been one of the most successful ad managers ever created. I think part of his success was due to the fact it was a SaaS based product, developed when SaaS was not even a word :)

DFP allowed to:

- organize campaigns, creatives, orders, line items, etc. Many obscure terms I will not explain here. I will only explain what is needed to understand the rest of this article, btw.

- serve the most valuable creative amongst the closed deals

- track, analyze, report - because after all, based on this data, advertisers will pay publishers!

Not all publishers had the resources for a dedicated sales team or the power to engage with the most valuable customers. Also, when campaigns are exhausted, there are no remnant ads to show and this can lead to blanks in some moments of the year. But things are going to change again because at some point in 2007...

Google acquires DFP

With the acquisition of DFP, Google does not change the original philosophy of DFP as an Ad Manager, but introduces a new element: instead of choosing ads from deals only, publishers can also include ads from AdExchange (abbreviated: AdEx). This means that when for an ad unit (the area to fill on the publisher's website) there are no ads to display, DFP could deliver an ad from Google's network of advertisers. These are good news for small publishers who could get ads from AdEx and do not base their incomes on direct sales only.

With Google acquisition, DFP also started to track users and display ads based on their navigation history. So if you navigate an exclusive watch website, you'll see the ad for that watch following you on other websites.

DFP has now been renamed in Google Ads Manager (GAM). I will use GAM for the rest of the article but the world is still calling DFP at the time of writing.

What happens when a browser asks for an ad to GAM

Let's pretend you're a publisher. To integrate GAM on your website you must create an account and configure it. I am not an expert in this field so I will not discuss this in detail. One important part, however, is that when you setup a "deal", you can insert the advertiser's creatives in the form of javascript code, and if this creative is selected for display, it will be injected in the user page inside an iframe. Keep this in mind: it is one of the foundation pieces of header bidding.

Let me introduce another important piece of terminology now, a "deal" is called Order in GAM words.

The next step is to integrate googletag code. This is a JS library that will make the request to GAM for an ad, that will be shown in a div on your website. Along with the request, googletag will pass some cookies trying to identify the user and only show ads that match the user interests.

googletag will take care of resizing and render the ad, track viewability (that means: has the ad been in the viewport for more than 1.5 seconds? if yes, publisher will be paid), and detect fraud. The internals are obscure, probably to avoid malicious attempts to reverse engineer and forge attacks.

An important aspect of googletag is that you can define custom key-value pairs along with the request, and this feature is called (in GAM terms) Targeting. A targeting example could be country=IT or interests=sports. GAM can be later configured to read these key-value pairs, and do some logic on them - like, if the user is from Italy and is interested in sports, show him ads from the important sports brand I have a deal with.

Why I said that it's important? well, Targeting is another key concept of Header Bidding. I'll explain later on.

Here is an example googletag call.

Is there life after Google?

In Ad tech terms, Google is a SSP - Supply Side Partner - meaning it will supply publishers with ads (and pay them). Are there other SSPs ? Yes there are, I guess more than 2-300, however the number of ads they can provide is much lower than that of Google and Facebook. An estimation is that 60% of all ads are traded by Google and Facebook, leaving the remaining SSPs trading the remaining 40%. So it's a tough market and many websites do not even think of substituting or integrating with other SSPs.

However, living with Google only is not the best option. Google does not make any effort to be transparent on how much ads have been payed, so some suppose that Google is showing us the most profitable ads for them - not for publishers.

Due to the fact that Google has the majority of the market, it is ignoring all other SSPs and does not offer an easy way to integrate them in DFP.

SSPs still have some advantages. For example, when asking for an ad to an SSP, we know exactly how much we're going to be paid if we render that ad, and this means we can start auctions amongst all configured SSPs and get the best priced ad. The price is usually given in CPM (cost per mille - cost per thousand impressions), so if an ad has a cpm of 10$, one single impression is worth 0.01$ ! (The average cpm, at the time of writing, is around 1$ if you were asking).

Interestingly, we can use this feature to deduce the price of GAM ads, too. How? Let's introduce...

Header Bidding

the name Header bidding (HB) comes from the fact that, historically, what I'm going to describe was done in the <head> part of the page. This is no more true, but the name remained :)

HB hacks GAM to allow other SSPs to bid for the same ad units. Let's recap the three foundational items:

- we can inject whatever creative we want for custom orders.

- we can define targeting on GAM requests, so we can display specific ads to some users.

- SSPs will tell us what they're paying us, and we can use this piece of information to estimate the price of GAM ads too.

You're finally ready to discover the HB process, for dummies:

- We start an auction for every ad unit on page. This means that we ask a bunch of SSPs (except Google, at this stage!) how much they are willing to pay if their ad is chosen.

- SSPs will answer with their responses, and we choose the SSP with the highest value. SSPs will also answer with the ad to render, we will store it in memory and render in the next stage.

- We send to GAM a request by setting some targeting keys: among them, we set the SSP name that has the best offer (for reporting) and the price of the ad.

- When GAM receives the request, it will decide what to do according to a specified set of rules. if AdEx has an ad that has an higher value, it will return AdEx ad. Otherwise, it will return the creative that has been specified by us.

- If the returned creative is the piece of javascript we defined, this means that the SSP won against GAM too, and the creative will contain only one instruction: render the ad that has won the auction at step 2.

How can we infer the price of a GAM ad ? By GAM terms of service, GAM is obliged to send us an ad that costs at least 0.01 cpm than the one we sent at step 3. So if the SSP ad was priced 0.26, we know GAM ad is worth at least 0.27 .

Prebid.js

What you've just read here is nothing more than the logic behind PrebidJS, an open source project born as a synergy between the SSPs community.

Prebid will perform the auction amongst the publisher chosen set of SSPs, then will query GAM, and finally will render the ad. Prebid also contains code to display video ads, mobile ads, handle different currencies, and much more.

Here you can see an example of prebid in action.

That's it?

That's definitely not all, folks! I've just scratched the surface of the ad tech world; I apologize if something is not clear (ask in the comments!) and probably I've generalized too much.

If you're a programmer, you'll be able to understand a lot of concepts that you'll encounter in the future. I've deliberately decided not to talk about many GAM concepts that are not worth introduce at this point, but you're highly encouraged to study if you want to succeed in this field. GAM alone has a big slice of market share of all ad tech servers and you'll for sure end up working on it, sooner or later ;)